As I grew up in Upstate New York, on a main line of the Underground Railroad and near the Harriet Tubman Home and Research center, I learned the lessons of slavery from the point of view of the Yankee victors. I spent the first several decades of my life knowing only that all slaveholders were horrible villains and all slaves were desperate victims. I spent another portion of my life in North Carolina, where I made some of my closest friends and married a North Carolina man. During those years, I learned to see Southern history from very nearly the opposite side, I learned about the aggression of the North, the heroism of the South, and the treachery of Northerners–however, I learned very little about the plight of slaves. My southern friends seemed nearly silenced by a cloud of guilt–they, as much as my original northern educators, assumed all slaveholders treated slaves badly, and all slaves were abused victims–and, generally, they just didn’t want to talk about it.

As I began to research 19th Century American History and Literature, and to write about the 19th century in the South, I found myself thinking that it could not be that simple, and I was driven to learn more about the slavery as it really was for the almost 250 years it was an American reality. While there is no saying that slavery was anything but a travesty, and an insupportable institution in all possible ways, I think it is instructive to examine how the institution grew and became more and more entrenched in response to a series of social and economic forces that do explain even as they do not justify. This adds some critical complexity to the picture of both the slave and the slaveholder who normally are viewed too simplistically to be credible. It does a disservice to the South to imagine all slaveholders were purely self-interested, dimwitted, and even diabolical Simon Legrees, as it does as well to imagine that all slaves were equally dimwitted passive victims.

Evolution of Slavery

In this post, I propose to examine how slavery became so deeply entrenched in Southern Society from 1600 to 1861 that people were willing to sacrifice all to maintain the system.

1600s

Although the number of African-American slaves grew slowly at first, by the 1680s they had become essential to the economy of Virginia. During the 17th and 18th centuries, African-American slaves lived in all of England’s North American colonies. Before Great Britain prohibited its subjects from participating in the slave trade, between 600,000 and 650,000 Africans had been forcibly transported to North America. (“Immigration,” Microsoft Encarta 98 Encyclopedia. Microsoft Corporation.) In the Americas, there were added dimensions to this resistance, especially reactions to the racial characteristics of chattel slavery. This fundamental difference from the condition of slaves in Africa emerged gradually, although the roots of racial categories were established early. Furthermore, slaves did not consolidate ethnic identifications on the basis of color, but it was widely understood that most blacks were slaves and no slaves were white.

Some Key Points:

- Value of Slaves: 1638 The price tag for an African male was around $27 (Equivalent to approximately $5,000 in 2012 dollars), while the salary of a European laborer was about seventy cents per day.

- First Fugitive Slave Law: Virginia colony enacts law to fine those who harbor or assist runaway slaves. (Underground Railroad Chronology, National Park Service). The Virginia law, penalizes people sheltering runaways 20 pounds worth of tobacco for each night of refuge granted. Slaves are branded after a second escape attempt.

- Spread of Slavery & Slave Regulations: Slavery spread quickly in the American colonies. At first the legal status of Africans in America was poorly defined, and some, like European indentured servants, managed to become free after several years of service. From the 1660s, however, the colonies began enacting laws that defined and regulated slave relations. Central to these laws was the provision that black slaves, and the children of slave women, would serve for life. This premise, combined with the natural population growth among the slaves, meant that slavery could survive and grow…

- Status of the Mother: Citing 1662 Virginia statute providing that “[c]hildren got by an Englishman upon a Negro woman shall be bond or free according to the condition of the mother”. Throughout the late 17th and early 18th century, several colonial legislatures adopted similar rules which reversed the usual common law presumptions that the status of the child was determined by the father. (See id. at 128 (citing 1706 New York statute); id. at 252 (citing a 1755 Georgia Law)). These laws facilitated the breeding of slaves through Black women’s bodies and allowed for slaveholders to reproduce their own labor force.

- First Rebellion: 1663/09/13 – First serious recorded slave conspiracy in Colonial America takes place in Virginia. A servant betrayed plot of white servants and Negro slaves in Gloucester County, Virginia.

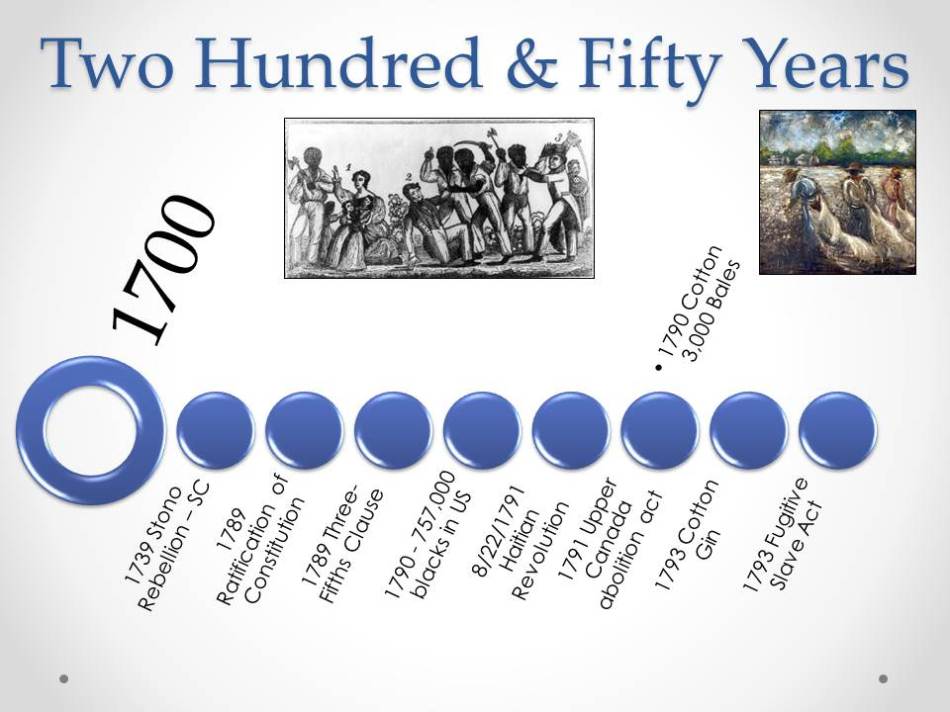

1700s

SOME KEY POINTS:

- Stono Rebellion 1739 South Carolina – Armed slaves, numbering over 80, attempt to march to Spanish Florida from their home area in South Carolina. When confronted by a local militia company organizes to suppress the rebellion, twenty-one whites and forty-four slaves die.

- Slavery Declining as an Institution by 1789 All the signs suggested that slavery was a terminal institution in the nation at the time of the ratification of the U. S. Constitution in 1789. Tobacco crop was exhausted. A number of northern states, had abolished slavery by 1800, and the federal Congress banned slavery from the vast region of unorganized territory north of the Ohio River with the Northwest Ordinance of 1787. Dozens of anti-slavery societies sprang up in the northern states and the upper South, and many enslaved African Americans openly challenged the system by suing for their freedom in state courts and by running away. Nevertheless, the ending of slavery did not happen for another 60 years-in fact, it took on new life in the new century, spreading rapidly from Georgia to Texas by 1830.

- Impact of Canada: 1791 Upper Canada (now the province of Ontario), was created in 1791 to cope with the influx of refugees from the American Revolution, was home to several hundred slaves, many of them brought there by their loyalist owners fleeing the new republics. Upper Canada’s first parliament, under pressure from Governor Simcoe, passed an act to gradually abolish slavery in the colony: No more slaves could be brought into Upper Canada. Those already in the colony prior to the Act were to remain slaves for the rest of their lives. The children of female slaves already in Upper Canada would be free upon reaching their 25th birthday. This Upper Canadian statute did not explicitly deal with the question of the rights of fugitive slaves who had escaped to Upper Canada but as a result of the legal opinion of the colony’s Chief Justice in 1818 no one seen as a slave in another jurisdiction could be returned there simply because he/she had sought freedom in Upper Canada. Whatever their status in the U.S. or elsewhere, in Upper Canada they were free long before the abolition of slavery throughout the British empire in 1833.

- Impact of Haiti: By this time, however, the concepts of the rights of man had spread to the slave class. In 1791, under the leadership of Toussaint l’Ouverture, the slaves began a long and bloody revolt of their own. Slaves flocked to Toussaint’s support by the thousands until he had an army much larger than any that had fought in the American revolution, This revolt became entangled with the French revolution and the European wars connected with it. Besides fighting the French, Toussaint had to face both British and Spanish armies. None of them was able to suppress the revolt and to overthrow the republic which had been established in Haiti.

- Jefferson was terrified of what was happening in Saint Domingue. He referred to Toussaint’s army as cannibals. His fear was that black Americans, like Gabriel, would be inspired by what they saw taking place just off the shore of America. And he spent virtually his entire career trying to shut down any contact, and therefore any movement of information, between the American mainland and the Caribbean island. He called upon Congress to abolish trade between the United States and what after 1804 was the independent country of Haiti. And of course, Jefferson then argued this was an example of what happens when Africans are allowed to govern themselves: economic devastation, caused in large part by his own economic policies.

- Fugitive Slave Act becomes a federal law. Allows slave-owners, their agents or attorneys to seize fugitive slaves in free states and territories.

- Cotton Changes Everything: Invention of the cotton gin in 1793. This relatively simple machine invented by Eli Whitney removed seeds and trash from the short-staple cotton easily grown in much of the South. Prior to the invention of the cotton gin, short-staple cotton had to be combed by hand before it could be spun into thread, a costly labor-intensive process. At the same time, England turned from wool to cotton for its textiles and began consuming with a ravenous appetite American cotton. The surge of cotton production from the U. S. jumped from 3,000 bales in 1790 to nearly 200,000 bales by 1812. It stood at 4,449,000 bales in 1860, with each bale weighing between 300 to 500 pounds. On the eve of the Civil War, the value of cotton exports amounted to over 50 percent of the value of all U.S. exports.

1800s

SOME KEY POINTS:

- 1808 Slave importation outlawed. Some 250,000 slaves were illegally imported from 1808-60. Importation of slaves into the United States is banned as of January 1 by an act of Congress passed last year, but illegal imports continue (see 1814). Some southerners feared slave revolts if importation continued. Religious societies stressed the moral evil of the trade, and free blacks saw the end of the slave trade as a first step toward general emancipation.

- American Colonization Society founded. It was considered the ideal solution to the American racial dilemma. Claiming to be interested in the welfare of the African in its midst, the Society advocated colonizing in Africa or wherever else it was expedient. It comforted slave owners by announcing that it was not concerned with either emancipation or amelioration. Both were outside its jurisdiction. It did imply that slaves might eventually be purchased for colonization. Most of its propaganda tried to demonstrate that the freedman lived in a wretched state of poverty, immorality, and ignorance and that he would be better off in Africa. The movement received widespread support from almost all sectors of the white community including presidents Madison and Jackson. Several state legislatures supported the idea, and Congress voted $100,000 to finance the plan which eventually led to the establishment of the Republic of Liberia. However, the Afro-American community was not very enthusiastic about the project. In 1817 three thousand blacks crowded into the Bethel Church in Philadelphia and, led by Richard Allen, vehemently criticized colonization.

- Nat Turner Rebellion 1831, African-American slave and revolutionary; b. Southampton co., Va. Believing himself divinely appointed to lead his fellow slaves to freedom, he commanded about 60 followers in a revolt (1831) that killed 55 whites. Although the so-called Southampton Insurrection was quickly crushed and Turner was caught and hanged six weeks later, it was the most serious uprising in the history of U.S. slavery and virtually ended the organized abolition movement in the South.

- President Adams on Slavery: At a dinner in Boston, Alexis de Tocqueville, a young French magistrate who would go back home to write his classic book “Democracy in America,” was seated next to former President John Quincy Adams and asked the old man: “Do you look on slavery as a great plague for the United States?” “Yes, certainly,” Adams answered. “That is the root of almost all the troubles of the present and the fears for the future.”

- 1838 “Underground Railway” organized by U.S. abolitionists transports southern slaves to freedom in Canada, but slaving interests at Philadelphia work on the fears of Irish immigrants and other working people who worry that freed slaves may take their jobs. A Philadelphia mob burns down Pennsylvania Hall May 17 in an effort to thwart antislavery meetings. (The People’s Chronology 1995, 1996 by James Trager from MS Bookshelf.)

- Secret Codes in Quilts: A book, co-authored by a professor at Howard University, pieces together a story of how quilts made by slaves before and during the Civil War were stitched with patterns that formed a secret code, part of a network of communication that helped slaves escape to freedom.

- The Compromise of 1850was worked out by Henry Clay to settle the dispute between North and South. On January 29, 1850, it was introduced to the Senate as follows:

- California should be admitted immediately as a free state;

- Utah should be separated from New Mexico, and the two territories should be allowed to decide for them selves whether they wanted slavery or not;

- The land disputed between Texas and New Mexico should be assigned to New Mexico;

- In return, the United States should pay the debts which Texas had contracted before annexation;

- Slavery should not be abolished in the District of Columbia without the consent of its residents and the surrounding state of Maryland, and then only if the owners were paid for their slaves.

- Slave-trading (but not slavery) should be banned in the District of Columbia;

- A stricter fugitive slave law should be adopted

Where Things Were by 1861

By 1861, Slavery was deeply entrenched, mostly in support of the cotton trade. Cotton can be likened to the oil trade in the 20th and 21st centuries–it was what created a hugely wealthy society, and this wealth was entirely dependent on cotton and the slaves who produced it. While all realized this was not an ideal situation, all also saw no way out. So, Southerners did their best to validate the life they were leading, and slaves did their best to survive. The North also can be seen to be motivated to get a hold of this wealth as much as by any efforts to improve life for slaves.

In the next post, I will address the Southern Arguments for Slavery, and it the following one, I will discuss Surviving Slavery as I examine slave strategies to develop their own power as they survived.

You must be logged in to post a comment.